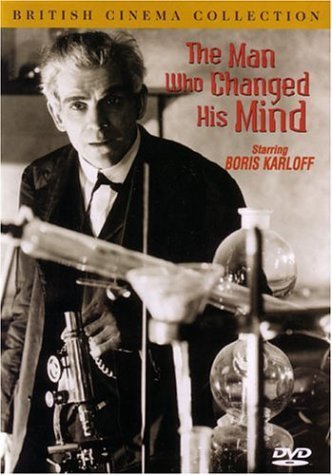

At the beginning of Robert Stevenson’s The Man Who Changed His Mind, we learn that the young Dr. Clare Wyatt is going to work with the aged Dr. Laurience (Boris Karloff, in one of his usual roles), a once-respectable scientist turned “mad brain specialist.” Laurience has invented a machine for relocating mental contents between brains. “Until now,” he explains to an increasingly worried Clare, “it’s never been possible to, as it were, extract the thought content from a living brain, and leave it alive but empty. I can do it; I can take the thought contents of the mind of a living animal, and store it, as you would store electricity.” As he demonstrates with two chimps, he can then transfer these contents to another living animal’s brain. When Clare realizes that Laurience wants to try this out with humans, she refuses to help him any further. The doctor seeks to convince her: “I can take a young body, and keep my own brain.” And he can do the same for her: “Think of it: I offer you eternal youth, eternal loveliness!”

Inspired by the homonymous book by Fernando Vidal and Francisco Ortega, this timespace presents the authors' genealogy of the cerebral subject and the influence of the neurological discourse in human sciences, mental health and culture.